Knowledge Networks and Communities of Practice

Roberta Comunian

The literature on learning and knowledge communities is very broad and has been a topic of extensive research across economic geography and organisational studies (for a review McKelvey, 1999). In this paragraph, we are specifically interested in the economic geography perspective as it focused on place and shared-spaces where learning and knowledge exchange happen, but there are of course strong connections with the aspect of online communities.

The literature acknowledges the strong relationship between individual and collective learning in the work context (Fenwick, 2008). Following Fenwick (2008) within this broad literature, we highlight these important dynamics:

1) Individual knowledge acquisition: in particular linked to the idea that alongside codified knowledge (which is easily transferable) there are sets of practice and knowledge that are tacit and hard to teach/explain and transfer (Gertler, 2003)

2)Sense-making and reflective dialogue: this seems particularly relevant for artists and craft makers. Many consider feedback from peer as pivotal to their development. “the collective is viewed as prompt for individual critical reflection, a forum for sharing meaning and working through conflicting meanings among individuals to create new knowledge” (Fenwick, 2008: p. 232)

3) Communities of practice (CoP): As Wenger (2006) explains “communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly”. Although this is a very broad and fluid definition, that can be applied both within and outside organisations, they are not stable or static but evolve and change. The focus is the interest shared by members of the community as being the common ground and reason for engagement and exchange. Although the communities of practice approach has many limits (Roberts, 2006) – specially in relation to the role played by trust, power and structures – it remains a useful framework to understand motivations and engagement amongst practitioners.

4) Co-participation or co-emergence: embedded in the complexity theory thinking, here the focus is on “mutual interactions and modification between individual actors, their histories, motivations and perspectives, and the collective (Fenwick, 2008: 236). The focus here is micro-interactions and its connections/relation with macro-level outcomes.

Much of the literature on learning and collaborative communities of practice is based on the main distinction drawn by Granovetter (1973) that individuals are embedded in both strong and weak ties and that they have distinct values and functions. While strong ties are based on shared experiences and values developed over time, weak ties are more temporal and require less investment and commitment.

The key role played by networks is linked to the intrinsic nature of creative work where temporary, project-based structures are common across different creative sectors and also where multiple roles and job handling the norm in the so called slash/slash professional identities are emerging (Gornostaeva and Campbell, 2012; McRobbie, 2002).

In the literature there is a key focus on investigating the difference in strength and value of ties and connections (Antcliff et al., 2007; Burt, 2004) however there is a certain agreement in reference to the fact that different kind of connections (and their relative strength or weakness) can all play different roles for individuals.

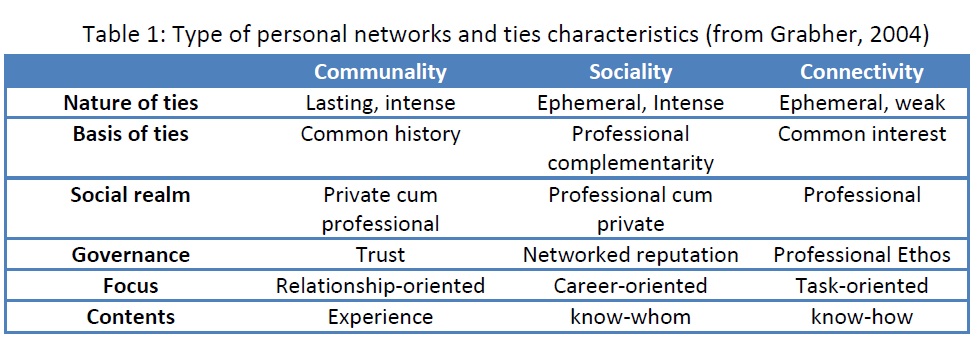

In particular Grabher (2004) considered specifically work in the creative industries and developed a different typology of personal networks for creative workers (table below). This is important as it highlights the range of connections and their shifting from professional to private and from long-lasting to ephemeral connections. What is shared is also important whether it is specific know-how or simply the sharing of contacts.

The literature on learning and knowledge communities is very broad and has been a topic of extensive research across economic geography and organisational studies (for a review McKelvey, 1999). In this paragraph, we are specifically interested in the economic geography perspective as it focused on place and shared-spaces where learning and knowledge exchange happen, but there are of course strong connections with the aspect of online communities.

The literature acknowledges the strong relationship between individual and collective learning in the work context (Fenwick, 2008). Following Fenwick (2008) within this broad literature, we highlight these important dynamics:

1) Individual knowledge acquisition: in particular linked to the idea that alongside codified knowledge (which is easily transferable) there are sets of practice and knowledge that are tacit and hard to teach/explain and transfer (Gertler, 2003)

2)Sense-making and reflective dialogue: this seems particularly relevant for artists and craft makers. Many consider feedback from peer as pivotal to their development. “the collective is viewed as prompt for individual critical reflection, a forum for sharing meaning and working through conflicting meanings among individuals to create new knowledge” (Fenwick, 2008: p. 232)

3) Communities of practice (CoP): As Wenger (2006) explains “communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly”. Although this is a very broad and fluid definition, that can be applied both within and outside organisations, they are not stable or static but evolve and change. The focus is the interest shared by members of the community as being the common ground and reason for engagement and exchange. Although the communities of practice approach has many limits (Roberts, 2006) – specially in relation to the role played by trust, power and structures – it remains a useful framework to understand motivations and engagement amongst practitioners.

4) Co-participation or co-emergence: embedded in the complexity theory thinking, here the focus is on “mutual interactions and modification between individual actors, their histories, motivations and perspectives, and the collective (Fenwick, 2008: 236). The focus here is micro-interactions and its connections/relation with macro-level outcomes.

Much of the literature on learning and collaborative communities of practice is based on the main distinction drawn by Granovetter (1973) that individuals are embedded in both strong and weak ties and that they have distinct values and functions. While strong ties are based on shared experiences and values developed over time, weak ties are more temporal and require less investment and commitment.

The key role played by networks is linked to the intrinsic nature of creative work where temporary, project-based structures are common across different creative sectors and also where multiple roles and job handling the norm in the so called slash/slash professional identities are emerging (Gornostaeva and Campbell, 2012; McRobbie, 2002).

In the literature there is a key focus on investigating the difference in strength and value of ties and connections (Antcliff et al., 2007; Burt, 2004) however there is a certain agreement in reference to the fact that different kind of connections (and their relative strength or weakness) can all play different roles for individuals.

In particular Grabher (2004) considered specifically work in the creative industries and developed a different typology of personal networks for creative workers (table below). This is important as it highlights the range of connections and their shifting from professional to private and from long-lasting to ephemeral connections. What is shared is also important whether it is specific know-how or simply the sharing of contacts.

Of course networks and learning are set in specific times and spaces. In fact, in the context of performing arts and festivals time and space play a specific role.

As mentioned before one important dimension of the way knowledge and expertise is developed and learning is related to ‘tacit knowledge’. Tacit knowledge is sticky (often linked to a person or a place/organisation) and learning cannot happen in a codified way (through a manual or an explanation) but needs to be transferred through practice, observation, doing or sharing. There is a wealth of literature considering the role of these important dynamics and of course time and space play a key role as they often imply a co-presence and co-location (Lundvall and Johnson, 1994). The concept of ‘learning-by-doing’ highlight the need for demonstration and practice to be shared (Arrow, 1962) but also the concept of ‘learning-by- interacting’ (Lundvall, 1992) underlines the role played by exchange and feedback.

The key role played by networks is linked to the intrinsic nature of creative work where temporary, project-based structures are common across different creative sectors . While this literature mainly focuses on business fairs and temporary exhibitions, many of the knowledge dynamics described can be considered relevant for the kind of knowledge networks and learning that takes place in festivals. Bathelt and Schuldt in particular consider two many set of interactions within the context of temporary fairs:

1) Vertical interactions: this mainly corresponds to interaction, which involve customers or suppliers. In a craft context this can be interaction with audiences (in reference to satisfaction), customers who buy craft or attend craft events but also organisers of craft events or platforms (online and offline).

2) Horizontal interactions: relates to interactions which involve other craft makers

The authors highlight the importance of contacts and exchanges taking place during temporary events such as international fairs. In particular they highlight the importance of learning through comparison and observation. They also consider the value of scouting for complementarity (in reference to suppliers or possible partners).

As mentioned before one important dimension of the way knowledge and expertise is developed and learning is related to ‘tacit knowledge’. Tacit knowledge is sticky (often linked to a person or a place/organisation) and learning cannot happen in a codified way (through a manual or an explanation) but needs to be transferred through practice, observation, doing or sharing. There is a wealth of literature considering the role of these important dynamics and of course time and space play a key role as they often imply a co-presence and co-location (Lundvall and Johnson, 1994). The concept of ‘learning-by-doing’ highlight the need for demonstration and practice to be shared (Arrow, 1962) but also the concept of ‘learning-by- interacting’ (Lundvall, 1992) underlines the role played by exchange and feedback.

The key role played by networks is linked to the intrinsic nature of creative work where temporary, project-based structures are common across different creative sectors . While this literature mainly focuses on business fairs and temporary exhibitions, many of the knowledge dynamics described can be considered relevant for the kind of knowledge networks and learning that takes place in festivals. Bathelt and Schuldt in particular consider two many set of interactions within the context of temporary fairs:

1) Vertical interactions: this mainly corresponds to interaction, which involve customers or suppliers. In a craft context this can be interaction with audiences (in reference to satisfaction), customers who buy craft or attend craft events but also organisers of craft events or platforms (online and offline).

2) Horizontal interactions: relates to interactions which involve other craft makers

The authors highlight the importance of contacts and exchanges taking place during temporary events such as international fairs. In particular they highlight the importance of learning through comparison and observation. They also consider the value of scouting for complementarity (in reference to suppliers or possible partners).

Project completed in 2012